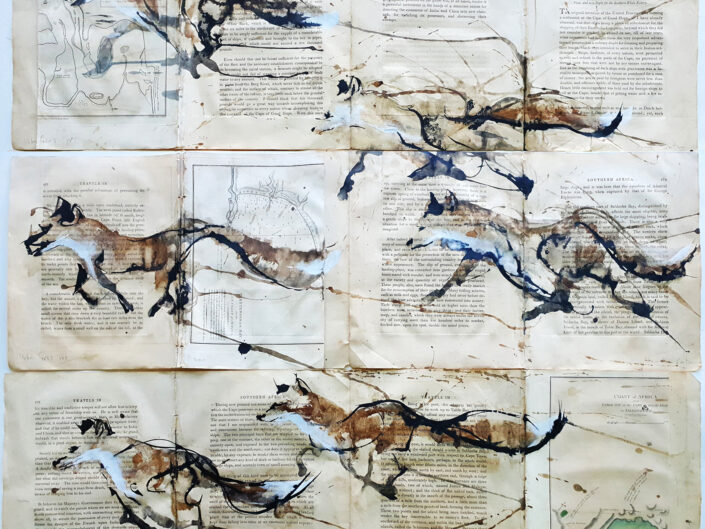

2015 Eland and Benko

Nirox sculpture park presents an Art/Science fire-grazer partnership where visual artist Hannelie Coetzee and Wits scientist Sally Archibald thoughts intercept. The work researches the relationships between things. Antelope/fire and fire/grazing and grazing/peoples perceptions and peoples perceptions/land management. Etc.

The Cradle of Humankind team from Working on Fire (WOF) will ‘perform’ the controlled burn of ‘Eland and Benko’ 2015.

Hannelie’s practise explores humans’ relationships with nature and how it evolves for the younger generation. She will document and interpret this process and the changes that occur. The relation between land, fire, antelope and the audience will be captured on film in collaboration with Reney Warrington.

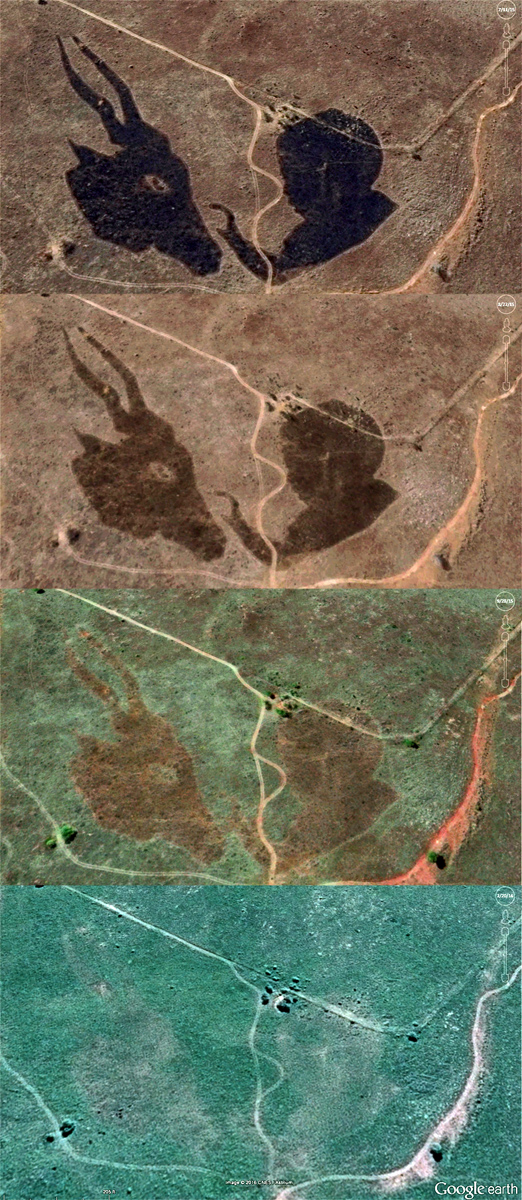

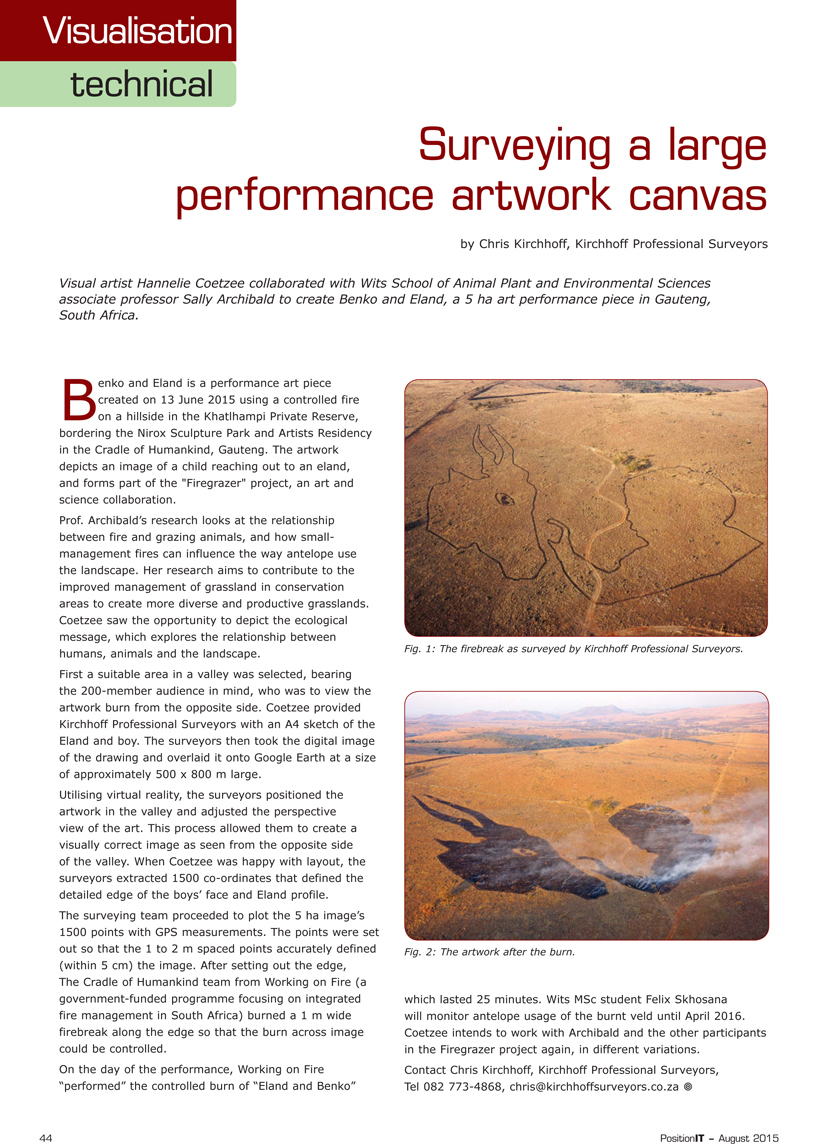

Sally’s research tests whether small management fires can create more diverse, more productive grassland communities by altering how antelope use the landscape. Wits MSc student Felix Skhosana will monitor antelope usage of the burnt veld. Kirchhoff Professional Surveyors plotted the 5Ha image with 1500 points.

Fire Place: Science and art burn bridges

On a 5ha hillside in the Khatlhampi Private Reserve, which borders on the Nirox Sculpture Park and Artists Residency in the Cradle of Humankind, a massive image of a child reaching out to an eland has been burnt into the grass.

The grace of the firefighters in the afternoon light made for a stirring spectacle. The silhouetted figures, titled Benko and Eland, form part of a remarkable project, dubbed “Firegrazer”, in which art meets science and broadens the scope of both.

Artist Hannelie Coetzee, fresh from a month at Wanas Konst in Sweden where she produced a 7m-high image of a wild boar made from branches and tree trunks, and known for her almost Bansky-ish mosaics and angle-ground images on urban walls, collaborated with scientist Sally Archibald to create this work. Archibald, an associate professor at the Wits School of Animal Plant and Environmental Sciences, has been carrying out experiments in various landscapes dealing with the relationship between fire and grazing animals, and how small- management fires can influence the way antelope use the landscape. Her research aims to contribute to the improved management of grassland in conservation areas to create more diverse and productive grasslands.

Coetzee recognised the potential for a large-scale ecological artwork in Archibald’s scientific practice. She thought that the spectacle of the burning, carried out by Working on Fire, an NGO specialising in controlled savannah fire management, and the scale of the markings of the landscape presented “a rich medium” in which to communicate the meaning behind the scientific project, bringing a dimension of human experience to the science, and scientific exploration to art.

She also saw the opportunity to convey a broader ecological message, exploring the relationship between humans and the landscape. About 200 people accompanied Coetzee, Archibald and MSc student Felix Skhosana, who is working with Archibald on the experiment, to watch the burn. They hiked 5km to the hillside opposite the burn site. Surveyors had plotted the image with 1500 points and an outline had been burnt into the grass ahead of the performance. The breathtaking precision and unintended grace of the teams of firefighters working in the late afternoon light made for a stirring spectacle. As the smoke cleared, the image was revealed, and the audience broke out into spontaneous applause.

The effect of the performance and the image left in the landscape was undeniably powerful, but Coetzee is not interested in beauty for its own sake, or art for communication or critique alone. Rather, she is interested in the ways in which artworks can participate in the social or environmental context they take place in, and contribute to the life around them.

Coetzee believes there is undiscovered potential in the crossover between art and science in the Firegrazer works, whether for science, land management or for the benefit of local communities. She intends to work with Archibald and the other participants in the Firegrazer project again, in different variations. The first Firegrazer performance and artwork represented art seeking and understanding its own potential in a new context. Subsequent performances can only enrich that understanding.

Graham Wood