2022 Impact Prize

A Still Life, Johannesburg

A Still Life, Johannesburg

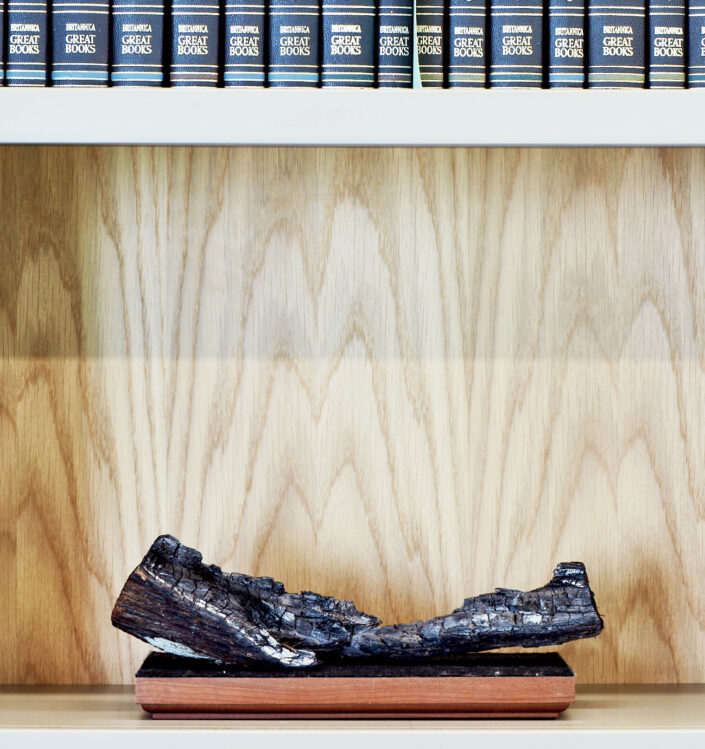

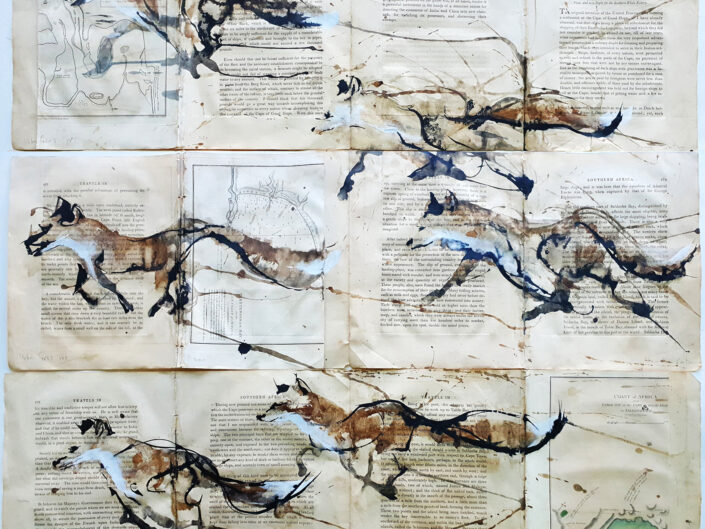

The Johannesburg gold rush drew a cacophony of humans who planted trees to remind them of home. Many trees were centenarian species, unlike indigenous trees which grow for a short 3 to 4 decades. Over time we came to understand how many of these trees classified as alien invasives were affected the highveld savanna ecology. Some naturalised. Some are thirsty, like Jacarandas. Likewise, Eucalyptus trees cause grassland ecology inhibition. The introduction of these “aliens” transformed the ancient savanna ecology into an urban forest so optimal that by the time the polyphagous shot hole borer (PSHB) beetle found itself in Johannesburg it could only flourish. As the beetles, with their heavy female reproductive bias excavate the soft tissue in the tree ring, the trees can only adapt or die.

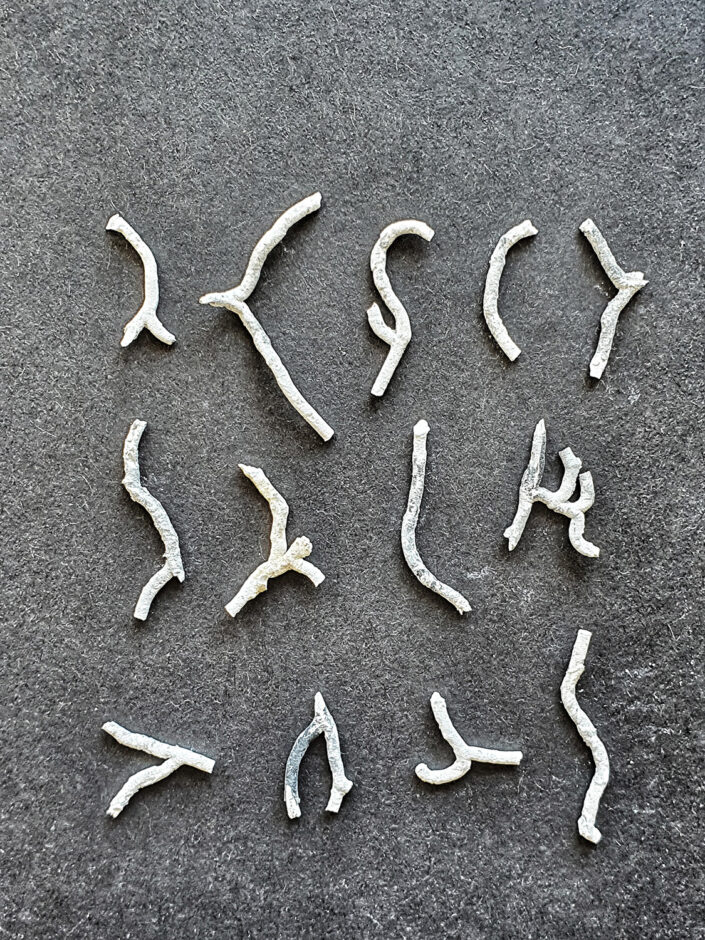

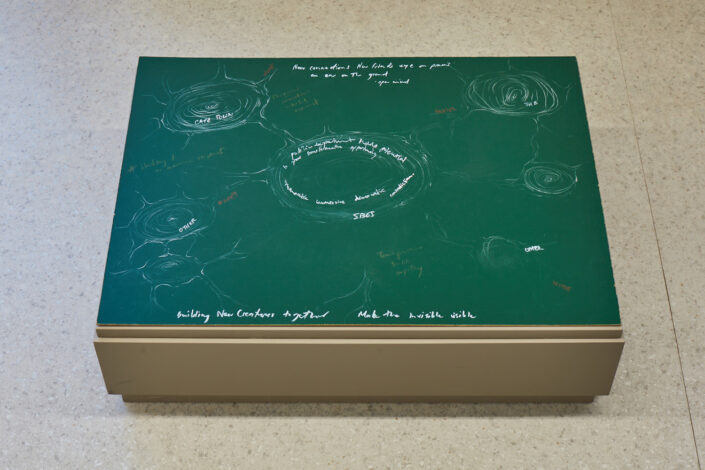

A Still Life-Johanneburg has presented the opportunity to deep dive into the beetles’ galleries, understanding how this causes the death of trees. The process has offered a moment to reflect on death and dying, in parallel to the scientific interrogation of this apparently wicked challenge. I have had the luxury to contemplate withness, and to unlearn definitive assumptions about what is good or bad. Through various sculptural processes I have worked to make the invisible, visible: injecting porcelain into the beetle galleries and firing them out; creating new creatures with walk talk friends; learning about the tree from multiple perspectives; and working out ways to grow healthier futures with more dynamic urban tree selection.

Hannelie’s video link (scratching Ash)

https://youtu.be/ybx9JETP1QA

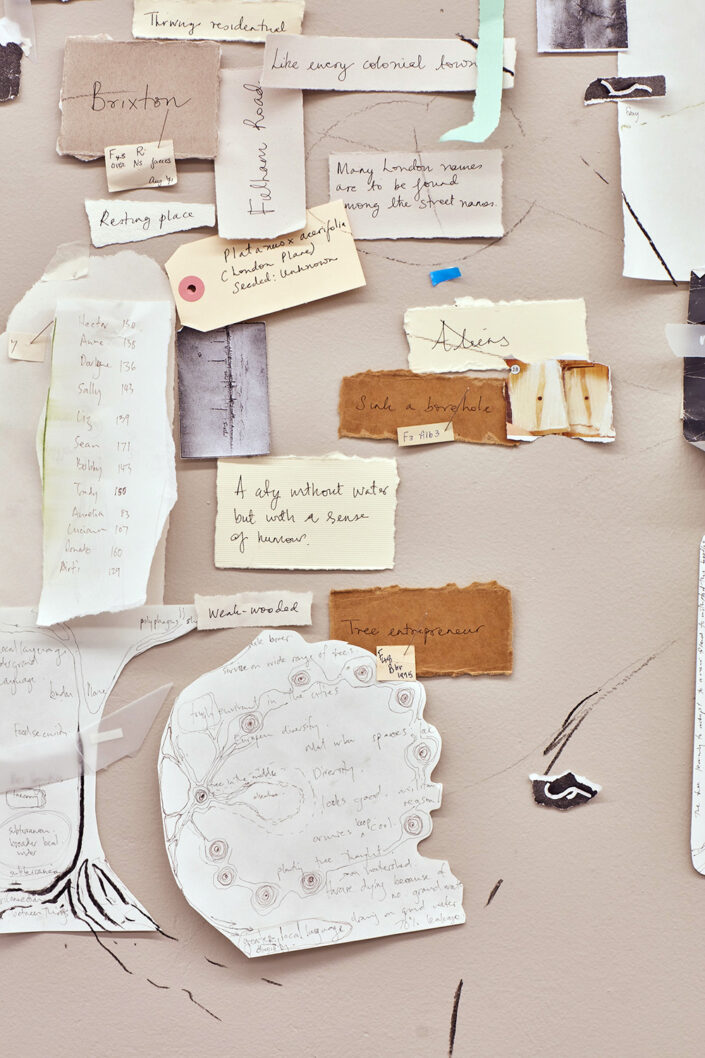

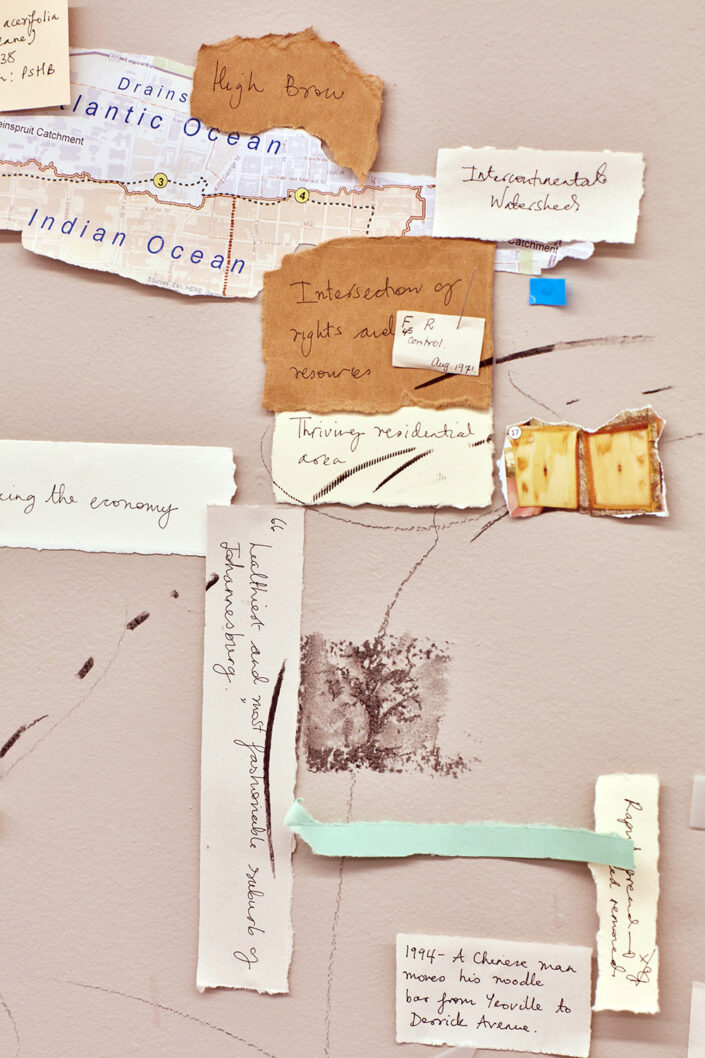

A Still Life: Johannesburg identifies three trees in Brixton, Cyrildene and Hillbrow to use as lenses through which to interpret the ecosystem of human, plant and city life that makes up a complex and interconnected urban environment. These dead or dying trees are infected with polyphagous shot hole borer (PSHB), which is said to threaten around 30% of Johannesburg’s population of trees. While acknowledging the impending loss of these trees, A Still Life is interested in the narratives that can be drawn from them and their environments – how these stories might enable us to see the city differently.

The borer beetle tunnels into trees to create what are known as ‘galleries’, where they lay their eggs. A fungus, ‘ambrosia’ is introduced to the tree by the beetles, providing food for their larvae when they hatch. The growth of the fungus impedes the vascular system of the tree while the borer’s ‘galleries’ undermine its structure. Although the borer, fungus and tree have a harmonious relationship in other parts of the world, this codependency has not been established in Johannesburg, with trees unable to withstand the effects of the beetle’s occupation.

Many of the trees that make up the ‘urban forest’ of Johannesburg are a colonial marker, representative of attempts to ‘Europeanise’ the landscape, which was once made up primarily of grassland vegetation. Non-indigenous trees such as Pine, London plane and English Oak were introduced both for aesthetic reasons as well as to facilitate mining operations. Centuries on, the Johannesburg landscape is in many ways defined by these trees that line its streets and shade its human and nonhuman residents. In years to come the spread of the PSHB is predicted to transform this landscape once more.

A Still Life positions itself in relation to dead and dying trees, carefully considering the histories they represent and the movements and changes they have witnessed during the course of their lives. The project is a collaborative initiative led by Taryn Millar, Sarah Cairns and Aarti Shah. A Still Life: Johannesburg is the second iteration of the project, with the first having taken place in Cape Town in 2021. For this iteration, Millar, Cairns and Shah are working with artist Hannelie Coetzee in developing a series of artistic interventions with the three dead or dying trees at their centre.

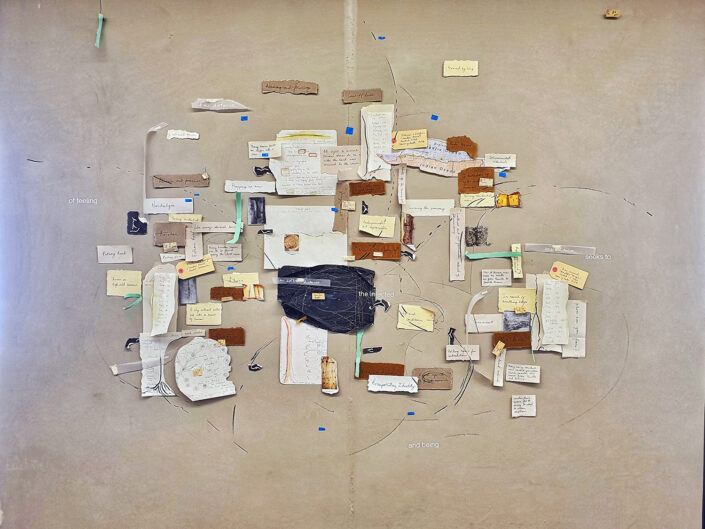

A key reference point for the project is the concept of a walking methodology, an experiential approach to research that foregrounds sensory responses in understanding a particular site or environmental subject. A Still Life invited community members, writers, scientists, historians, city officials and arborists to join them on a series of walks in Johannesburg in order to gain insight into the trees at the core of their project. Each participant was provided with a canvas bag, which included a notebook, pencil and space for a phone, keys and other basic necessities. The bag provided a connection between participants, serving as an indicator of the intention behind the walks – that is, to develop (as a group) a careful understanding of the social, political and historical conditions of spaces in which the trees have lived and died.

These walks and the sketches and writings that are drawn from them, form the basis of a multidisciplinary response by A Still Life that “…pays homage to trees, the lungs of our cities, and celebrates the on-going cycles of life and death in these non-human city dwellers.”[1]

It is rare now for people to live in the same place from birth to death.

A tree is seeded and lives in one place as people and communities come and go.

Its life unfolds alongside many others (human and non-human).

In some ways, it remains still as we go about our daily lives and in other ways, the tree does what it does as a tree, changing and adapting to its environment.

Trees help shape our sense of place. Someone’s thought led to a particular tree being planted in a particular place, maybe for how it looked or for its shade or for its wood. Johannesburg claims to be home of the largest man-made forest in the world.

Dying trees change our sense of place. Around 30% of Johannesburg’s trees are threatened by a small insect called the polyphagous shot hole borer, an ambrosia beetle. These creatures have been described as an alien invasive species, brought out unintentionally, it is thought, in wooden pallets on a ship from South-East Asia. The beetles have made homes in the trees of Johannesburg.

They don’t want to kill their hosts. We have heard this before.

They don’t want to kill their hosts, but the new environment they find themselves in is fertile ground for feeding their young. The beetles burrow a network of small tunnels deep within the tree. These are called galleries. The beetles carry fungus on their bodies through these galleries and plant them for their babies to feed on. Without the beetle, the fungus would only travel on a vertical plane up vascular pathways. As the beetle moves around inside the tree, it spreads the fungus throughout. The fungus compromises the tissue that transports water in a tree. With time, without water, the tips of the tree’s outermost branches begin to die. Death creeps towards the inner part of the tree. Some trees will die, and some will survive.

It is uncertain as to how many generations it will take for the beetles to assimilate and learn to live with their hosts without killing them, or whether they ever will, as many other beetles do, as many species do. The meeting of the shot hole borer beetle and the trees of Johannesburg, both alien and indigenous, has left traces of vulnerability and resilience throughout the tree-lined streets of the city. The relationships these trees have with one another are invisible. But the life that lives in and among the dying trees can sometimes be seen and heard. We miss so much when we don’t listen. There is still life in death.

The city is an entangled web of people, place and nature. The built environment and nature meet at every turn. Each place carries stories of pasts, presents, and imagined futures. The rhythm of our bodies moving through place helps us to listen closer. It helps us to connect, connect to ourselves, to each other and to our environments. It helps us to process grief and feel hope.

Walking and talking offers us different ways of listening and witnessing, of seeing and being, of feeling and responding. With each walk we carry a bag.

The bag is made from artist’s canvas, a nod to the artist in a walking-thinking-drawing routine. It holds pouches and pockets for tools such as pencils, paintbrushes and tweezers, epistemic objects and specimens, a map, a phone, and car keys. It is to be used across disciplines.

The act of wearing the thick strap on our shoulders places us in dialogue with one another. We are forming a community and creating space for collective thinking. These bags are gifts that keep giving and keep asking you to give; they are generative.

The seams that suture the bags together are on display, inside out. We hope to make the invisible, visible, because so much happens behind closed doors with narratives made by those in power dominating discourse.

The edges are frayed, blurring boundaries and revealing the process of making. We hope not to distinguish between the beginning and the end, much like the cyclicality in nature. The fraying of a bag is a slow process, slowing down our thoughts and our actions. We pick away at the threads of certainty with care, whilst ensuring that the bags don’t completely unravel. Through use, each bag will fray further in its own way.

The bag includes a book. The bag and book are a constant, present at different places and at different times of the day. Both carry marks of a process. These marks are the traces of singular and repeated encounters with people, place and nature in a city. They are much like the trace the beetle leaves in a tree and the trace of a tree’s shadow that once fell on a pavement.

The marks and the traces, the walks and talks, the beetles and the tunnels, the dying trees and their shadows, and people and their places are all connected.[2]

[1] A Still Life, 2022

[2] A Still Life, 2022